Sunday, October 30, 2011

“Analog” versus “Digital” in Games

Blogs are informal, and occasionally allow the writer to indulge himself, as in discussing his pet peeves. One of my pet peeves is the misuse of the terms analog and digital to represent non-electronic games and electronic games. I prefer the terms tabletop and video because they are more mellifluous and more directly address what people typically mean when they say analog games or digital games. I use video rather than computer because of the odd notion in many quarters that game consoles don’t count as computers. (They’re just limited and specialized computers, computer wannabes, really.) So I have to use video in order to include consoles. Baseball is an analog game, but sports are not usually what people mean when they talk about “analog games”, nor are they talking about “tag”or other children’s games. They usually mean games played at a table.

Something that is analog is continuous without discrete units or detents. Time is analog although we try to divide it into smaller and smaller pieces. Sound is also analog, although we have been able to divide it into such small parts that we can’t tell the difference between the digitized sound on computers and music CDs as compared with actual sound. ¹(Definitions from Dictionary.com at the end of the article.)

Something that is digital is divided into discrete units with nothing in between. The result of a die roll is digital: it’s a number one through six and cannot be 1 ½ or 2 3/4. Modern computers do everything in “ons” and “offs” (1s and 0s), hence they’re digital.

There are analog computers, such as a slide rule for those who remember such things. In World War II one of the reasons to develop digital computers was to replace the analog computers that were laboriously used to calculate ballistics tables for artillery.

You can see then that many tabletop games are in fact digital. Therefore it makes no sense to use “digital games” for electronic games. Nor does “analog games” work for non-electronic games. I actually used “electronic” and “non-electronic” for a while, but they are too cumbersome. So I substituted “tabletop” where that’s appropriate (again, baseball is not a tabletop game, but is a non-electronic game). And I substitute “video” (or sometimes “computer”) for electronic games.

While I am probably fighting against a tidal wave, I can only say that using “analog” to describe tabletop games and “digital” to describe video games does not make sense.

Analog:

adjective

of or pertaining to a mechanism that represents data by measurement of a continuous physical variable, as voltage or pressure.

Digital:

adjective

5. electronics: responding to discrete values of input voltage and producing discrete output voltage levels, as in a logic circuit: digital circuit

3. representing data as a series of numerical values

4. displaying information as numbers rather than by a pointer moving over a dial: a digital voltmeter; digital read-out

1. of, relating to, resembling, or possessing a digit or digits

2. performed with the fingers

¹Yes I know there are still people who claim that they can tell the difference between analog sound and digital sound, and there are a few nuts who claim that digitized sound is destroying modern ears.

Friday, October 28, 2011

"Thugs"

I’ve observed D&D players for more than 35 years, and one consistent observation is that the majority of them play characters who are essentially Chaotic Neutral thugs. This is particularly true if they’re not in a long-term campaign. They’re happy to go around beating up other creatures, killing the ones that they can get away with killing (that is, the monsters or the evil types), mugging those they may not kill, and getting whatever useful stuff they can extract out of people or other creatures. The ideal of “hero” only goes so far, sometimes doesn’t go anywhere at all, though there are also many players who are quite willing to be heroic in the game.

There are various levels of “thug”, and a lot worse than thug, such as the people who are entirely self-indulgent, will do whatever they want, and don’t care about what happens to their fellow party members. Often the completely self-indulgent players are below the age of majority, but it can happen at any age. I think of D&D as a highly cooperative game, and such people are nearly impossible to work with. On the other hand I can work with thugs–sometimes.

I had an example of thuggishness at a recent “D&D Encounters” session that I play in at a local game shop. D&D Encounters is organized by Wizards of the Coast to help introduce people to D&D. It is a series of connected sessions with a story of sorts, though the major purpose is to have battles. This seems partly to be built into 4th edition D&D, though some of this battle orientation is unavoidable because the sessions are open to whoever happens to walk-in and so we often have new players who don’t know the story or have any history with the group. Over the course of playing since last winter there are only two players (including me) left from the original group that was large enough to play three sessions simultaneously. I started playing to learn about 4th edition D&D and continue because I sometimes get boardgames playtested after the D&D, and because I like the other person who has been with it from the beginning. Over the course of that time we have played three “seasons”, so I am now with my third character that I have run up from first level to third.

So while the game is highly linear, which tends to be associated with a strong story orientation, in practice there isn’t much story because players change so often.

In general at these sessions people are willing to be the good guys and do what’s required to have the adventure, if only because there’s no alternative. There can be lots of hostile byplay between characters, though, and at least one character was killed by his own party on a day I wasn’t present (though knowing the character, I have to say he was asking to get dead).

But at the end of this recent adventure we ran into problems. We had defeated the enemy, and clearly our final task for the “season” was to pursue and defeat “the heir”, the bad guy. As the fight ended, some civilians came out of a nearby building and gave us some information and then a “general” who was more or less second-in-command in what was left of the city came up to ask us to go defeat the heir. It was a rather odd interjection, as we were clearly going to dothat anyway because that’s what the linear D&D Encounters calls for.

It is typical in RPGs that if you’re always a good guy and never ask for any benefit you may not get one. So when my female character spoke to this “general” who was asking us to take on the bad guy alone while her troops protected what was left of the city, I asked if she had any magic items that she could lend or give us that would help us in the last battle. She said no but if we used her name with the merchants we might be able to get good deals if there were any to be purchased (though this would be after the final battle, of course). In the circumstances, with what is left of the city more or less falling down around us owing to plague monsters, I thought that was the best we could get and I was ready to go on.

But some of my colleagues thought otherwise. (I might interject here that all but two of the players are 18 to 20 years old, and that includes the referee who is not highly experienced. I’m three times their age and there’s one other player who is in between my age and theirs. He is regarded as the “talker” of the group, because they aren’t keen to do the talking, and I tend to keep my mouth shut so as not to control things too much.) So the talker and one or two of the others essentially tried to verbally shake down this general to get more benefits-- starting the thug behavior that I’m talking about. I put both hands over my mouth, to the amusement of the referee, because I wanted to let things play out however they were going to play out. And the way they played out was that the referee, who has already shown himself to be fairly extreme in his points of view and reactions at times, played the general as quite offended. We came to a point where part of our party threatened to refuse to go after the bad guy (the heir) even though that would mean the end of the city. And the general pretty much said “do your worst”! I finally spoke up and said I was going after the bad guy and went some distance away because I didn’t want to be associated with what was going on. The inexperienced referee finally asked the experienced referee of the other group, who is the local organizer of the whole business, what he could do. In the end that referee said well you can go to the stock rooms and shake these guys down for whatever they’ve got but meanwhile the city will fall down around your ears and that will be that.

The session ended at that point and we had a long discussion about the appropriateness of the thuggish behavior. My main point was that their attempted shakedown had failed, and so their behavior was not appropriate no matter what they thought of it. I said I had asked for something and got a concession and that was pretty clearly (to me) all we were going to get. When the ensuing conversation made this even more clear (I thought), then they should have given up rather than proceed to the ultimate shakedown. But there was lots of disagreement. No one seemed to think he or she had done anything wrong, though some of the people who seemed to agree with the shakedown artists while it was happening now said they were no part of it . . .

Thugs, gangsters, whatever you want to call it, that’s often the way D&D characters behave. I’m sure next week we’ll go on to take out the bad guy, and I hope that my efforts have separated me from my thuggish colleagues (not that it matters as that will be the end of the “season”), but it’s possible that we’ll get no benefit other than the knowledge of a job well done.

Much of playing with this group is about people-watching–they love to banter with each other (and talk over each other), and it takes a long time to get anything done-- and it was certainly interesting. But not good play.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

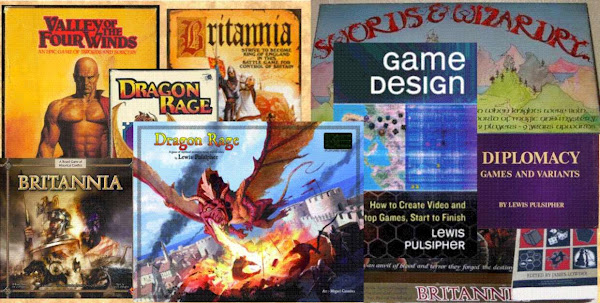

Dragon Rage news

Dragon Rage is available in the US for a limited time from Fun Again Games:

http://www.funagain.com/control/product?product_id=024826

A review of Dragon Rage appeared in a British blog. http://rivcoach.wordpress.com/2011/08/08/review-dragon-rage-from-flatlined-games/

Also on BGG.

http://boardgamegeek.com/thread/684165/boardgames-in-blighty-reviews-dragon-rage

A review of Dragon Rage on Opinionated Gamer.

http://opinionatedgamers.com/2011/10/04/review-of-dragon-rage-flatlined-games/#more-3873

Another review at Fortress Ameritrach.

http://fortressat.com/index.php/articles-boardgame-reviews/2898-dragon-rage-review.

Video review, in German, of Dragon Rage.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Nj-ZHlwA7I&feature=youtube_gdata

http://www.funagain.com/control/product?product_id=024826

A review of Dragon Rage appeared in a British blog. http://rivcoach.wordpress.com/2011/08/08/review-dragon-rage-from-flatlined-games/

Also on BGG.

http://boardgamegeek.com/thread/684165/boardgames-in-blighty-reviews-dragon-rage

A review of Dragon Rage on Opinionated Gamer.

http://opinionatedgamers.com/2011/10/04/review-of-dragon-rage-flatlined-games/#more-3873

Another review at Fortress Ameritrach.

http://fortressat.com/index.php/articles-boardgame-reviews/2898-dragon-rage-review.

Video review, in German, of Dragon Rage.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Nj-ZHlwA7I&feature=youtube_gdata

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

When you start a game design, conceive a game, not a wish list

This is something that should be obvious, yet despite everything I’ve written about beginners designing games I have not said it explicitly. And I know from my teaching experience that to many people it isn’t obvious. It is especially important for people who want to design video games rather than tabletop games.

When you set out to design a game it’s important to know what you want that game to do, what the impact will be on the players. But it’s much more important to know how the game is going to do that. Typically, beginners trying to design a video game will have visions of how wonderful it will be and how “kewl” and how much it will be just what they want to play, but if they try to solidify their notions they end up with a wish list of what they want the game to do, not a description of how the game is going to do it. And if you try to pin them down to how the game is going to do it they have no clue. (I don’t mean the details of programming, I mean the mechanics that the programming will enforce.) This is a special case of “hiding behind the computer”. The would-be designer completely loses track of the link between where he wants to go and where he is now, he more or less assumes that the computer will make it possible. “And a miracle occurs”.

What you want the game to do is part of the “idea”, how it will do it is part of the “structure”. As many have said, ideas are a dime a dozen. It’s the execution, the how, that makes a difference. The structure provides the framework for “how” to happen.

A wish list is OK, but if you don’t know how to get there you may just be describing your favorite game on steroids, your favorite game “to the max”. Frequently in such lists the would-be designer will say that he or she will have the best story ever, the best graphics ever, and so forth, which actually doesn’t mean anything at all. Because unless you know some practical method that will let you have the best story or the best graphics or the “best _____”, no one’s going to believe you’ll do it and it’s most unlikely to happen. In other words you’re wishing, not designing. In a sense it’s a form of fanboy-ism.

The tabletop game designer is less likely to fall into this trap because there’s no computer to hide behind. It’s much more obvious that the designer has to figure out the mechanisms the game will use to reach the desired result. This is yet another reason why it is more practical and more instructive to learn to design with tabletop games even if you intend to be a video game design.

Wednesday, October 05, 2011

Too many Choices?

Several people have pointed out that a major difference between wargames and Euro-style games is the number of (plausible) choices presented to a player when it is his turn. Wargames, especially the old-style (“traditional”) Avalon Hill hex and counter wargames like Stalingrad, Afrika Korps, Waterloo, and their descendants, offer vast numbers of choices to a player when it's his turn and he can move every one of his 40 or 50 units in a great variety of ways. Some of these choices are not plausible but a great many are. The great number of choices is one of the reasons why these games can have a lot of depth (“strategic depth” is the phrase sometimes used). There can be a lot of strategy in the game because there are a lot of choices. And it's to be noted that these are two player games, where you don't have the variables of the intentions of several other players and you don't need to worry about the impact of your choices on what those players might do to you. In a two player game you know the other player is your enemy, period.

In most Euro-style games you have relatively few plausible choices in your turn. In the Euro games where you're playing cards then you only have as many choices as the cards allow. You are often limited in the number of cards that you can have in hand as well. In Euro boardgames you often control very few pieces or units, and you are often quite limited in what you can do by action points or money or other resources.

This means that often players are "put on the horns of a dilemma" in choosing amongst the few alternatives that are available. And that's what games of strategy are about. But in wargames with many more choices, the dilemma is often greater.

In a multi-player wargame (such as Diplomacy) consideration of the intentions of other players increases the range of options when you play. On the other hand, even though most Euro-style games are for more than two players, there often isn't much direct interaction with other players. That means you don't have to worry as much about their intentions as in a wargame, again limiting the number of choices you have to make.

Concomitants of few choices

I'm convinced that this difference in the number of choices means that it's much easier to play a Euro-style game intuitively than to play a traditional wargame intuitively. To me when you have a large number of choices you have to use logic, as well as intuition, to effectively decide what to do. But I can't explain that conviction, as I think you could argue that when there are too many choices that's the time when intuition can be more effective than logic. Perhaps it's just that I play logically rather than intuitively, and I grew up with traditional wargames.

Another consequence of limited choice is that players can fail to pay attention for various intervals and still have a chance of using their intuition to choose an at-least-decent move. If you don't pay attention in a typical hex-and-counter wargame you're going to get your butt kicked by someone who is paying attention.

Limited plausible choices also means the player does not need much downtime to think about how he's going to move/play. In effect, each player's move is much less complex than in a wargame, but it takes much less time as well. In a sense it is as though you divided up the wargame turn into many separate turns. Yet the Euro games do not take longer than wargames, in fact typically less, and that may be because Euro games usually have more or less arbitrary turn limits. You play to a certain number of turns or points and then you're done, you don't have to dominate the opposition in the sense of wiping them out or capturing their capital or other distant/difficult objective that you would have in many traditional commercial wargames.

Transparency

Another consequence of the relatively small number of choices is that many Euro-style games are fairly "transparent," that is, after a player plays one game he often thinks that he knows the right things to do to win, and in many cases he's correct in that thought. This contrasts with many other games, especially some wargames, where you may have to play the game quite a few times before you come close to fully understanding the strategies involved. I'd cite my game Britannia as a case where playing once only begins to reveal the strategy of the game. People who are used to transparent Euro games sometimes play Britannia and complain that the game is badly unbalanced, because they have not yet begun to see what the various colors can actually do to influence/control the outcome.

This transparency is one of the reasons why Euro-style games are popular. After all, the origin of Euro-style games is as "family games on steroids," and while we are long beyond that with many Euro-style games, there is still this tradition that they should be relatively easy to "figure out" how to play well.

The transparency of most Euro-style games may help explain why so many of them are only played a small number of times. Players figure it all out quickly, then move on to the next game. Perhaps it’s more likely that a game with few plausible choices per turn is less likely to have the kind of depth that characterizes some games with lots of choices that people play dozens to hundreds of times.

Much of that transparency comes from the limited number of plausible choices players are typically faced with. If there are more choices than a player wants to deal with, "analysis paralysis" can set in. The player can't figure out what to do, and does nothing for an extended period., either not taking his turn, or doing nothing in his turn.

Resemblance of Euros to traditional card games

In respect of few choices Euro-style games of all kinds much more resemble cardgames than Chess or Go. In a card game you have a relatively small number of choices, represented by the cards in your hand. In typical traditional cardgames each card can only be used for one purpose such as playing it onto a trick in Bridge. A relatively simple boardgame like Checkers may have a similar number of plausible choices in each turn, but Chess or Go have many, many more.

In chess we have only 16 units on a side and only 64 locations on the board, but in many cases most of those units can move, and offer a variety of choices. The vital importance of each choice-- in a top class game if you make one mistake you may be doomed-- means that a player must consider a great many choices despite the small number of units.

On the other hand Tic-Tac-Toe (Noughts and Crosses) presents very few choices, which is one reason why a well played game always ends in a draw. Checkers presents many fewer choices than Chess or Diplomacy, but a lot more than Tic-Tac-Toe.

In Diplomacy there are only 34 units in the entire game yet seven players when it starts. Much of the richness comes from the fact that there are many players. There is a tactical richness in the movement of the units even though there are not a large number of choices, because movement is simultaneous and deterministic (no chance is involved in conflict resolution). The fact that there are many players and their intentions can make a big difference to what you do means that even with a few units that can be a great many plausible choices.

RPGs

For most RPG players I think RPGs tend toward the few choices and the intuitive side, which probably works better with the story style than with a wargame style. I play RPGs as wargames and see more choices and use logic much more to decide what to do. And I generally despise the story style because I hate not being in control of my own fate, yet in the story style the player often has to follow the story. (To me as a player, much of the purpose in a game is to control what happens. Stories imposed by the designer or referee don't allow this.)

Wizards of the Coast in 4th Edition D&D has changed the game to limit the number of choices, while at the same time assuring that every character has something to do every turn. Characters have relatively few powers, but these include some that can be used every turn.

Examples from a game club

I recently had this fundamental difference between Euro-style games and wargames brought home to me once again in my primary playtest group, which is the NC State Tabletop Gamers Club. The members of this club are college undergraduates, a few graduate students, and me. In my experience of groups of Euro gamers (who are usually much older on the average) people play as many different games as they can and few games are played over and over. At NC State several years ago, when the club was smaller, a lot more wargame-like games were played. Now the members play few games that have lots of choices, and their favorite games are games with relatively few choices for the player such as Betrayal at House on the Hill, Red Dragon Inn, Dominion, and Ascension. Boardgames seem to be played much less than in the past. One of the more popular boardgames is a prototype race and maneuver game I’m developing that has only five or six pieces per player.

What immediately brought this home to me was the following episode. One of our members likes to play Stratego, partly because she has a very good memory for pieces that have been temporarily revealed. She had played Stratego with her boyfriend a few weeks before, so I asked them to play a Stratego-like game that I have designed, tentatively called Solomons Campaign because it involves getting transports to the other side of the board in the midst of islands, submarines, surface ships, and airplanes of World War II vintage. But Solomons Campaign is a much more fluid and much less hierarchical game then Stratego. Immediately the young lady had some trouble with the rules, because there many more combinations possible and not the very clear hierarchy of strength from the Marshall down to the Scout that characterizes most of Stratego. The only departures from the strength hierarchy in Stratego are the bombs and the ability of the Spy to attack and kill the Marshall. In Solomons submarines can sink some ships when attacking, but cannot touch others (such as destroyers). But submarines lose to many ships and planes when attacked. The strongest ship (battleship) can't successfully attack the subs (but is not killed when attacking). The next strongest ship (aircraft carrier) wins when attacking a sub, but loses when attacked. Two planes can combine together to attack, such that two bombers can exchange with a battleship.

She was also thrown off because I believe that in a modern game people don't want to have to memorize the location of pieces, so in Solomons once a unit's identity has been revealed it stays visible; hence she didn't have the memorization advantage she felt she had in Stratego.

She also struggled setting up her pieces, because even though there are 25 pieces per player in this version of Solomons and 40 in Stratego, the hex board has many more locations (13 by 12 = 156) than the square Stratego board, so there is lots of room to set up the pieces. In Stratego there are 92 locations and 80 pieces altogether, and you fully occupy four rows when you set up. In other words there were vastly more setup choices in my game. In Stratego you just don't have very many places to put your pieces.

So altogether in Stratego you have fewer choices about where to set up, and as a result of the congestion on the board you have few choices of move when you start playing--only the front six pieces (lakes are in the way). In Solomons each piece has six directions it can go because of the hex board, instead of four (and can move one or two hexes straight in any of those directions). Furthermore, you can move two pieces at once if they're both airplanes. And airplanes can move over friendly pieces.

In actual play, the Stratego lover struggled because the game is very unlike Stratego in the number of choices each turn. Other games have shown that she is not good at figuring out strategy in wargames, like many people who aren't accustomed to playing wargames, so she suffered a form of paralysis quite strikingly. She just didn't know what to do strategically. Her boyfriend is more accustomed to wargames, and he ultimately made inroads on one flank and sent a transport through to win.

Even though the game is a distant cousin of Stratego, it is much more like a strategic wargame, and so less suitable for a mass market.

I recall one of the other members last year telling me that she did not care to play wargames because there were too many choices. (I think it was also because there tended to be too many rules to keep track of.) This young lady is one of the more intelligent people you would ever meet, but she plays tabletop games to relax and claimed that she relied on intuition as much as logic to make her moves. When there were too many choices, she said, she would just guess (or rely wholly on intuition, I'd say). She did play my other Stratego-like game (a space wargame, on squares, with just 19 pieces per side) and acquitted herself very well against someone who had played it three times before. That game is in between Solomons and Stratego in the number of choices.

As it happens these two examples are females but I don't think gender has anything to do with it. It's a matter of preferences that can turn up in males just as in females. 90% of the club members are male, yet the preference for games with fewer choices is widespread. It may be worth noting that the proportion of Euro players who are female seems to be much higher than the proportion amongst wargame players. This is similar to the proportions of hard-core and casual players of video games who are women (much higher in casual than hard-core). Whether this is because women are steered away from wargames when young, or “naturally” prefer fewer choices when playing games, or don’t care as much for “in your face” competition, or something else, I don't know.

Sunday, October 02, 2011

Cinematic RPGs and Huge RPG Books

At the UK Game Expo this summer I was part of a four-person panel of “RPG designers”. This was a little funny, because I’ve not actually designed an RPG from scratch, though I wrote a lot about them in White Dwarf and other magazines back in the day. (I was not on the game designers’ panel, but that was just as well as the British designers amounted to 10 or so people.)

One of the questions to the RPG panel was how much the particular game rules mattered to what kind of campaign the referee wants to run. For example, for a story-based campaign do you need a story-based role-playing game? I said any game could be adapted for any campaign, but another panelist, Sarah Newton of Cubicle 7, disagreed, and I can see why.

Sarah pointed me to a free RPG called Fate. This is about 80 pages of downloadable rules, associated with another, partially free RPG called Fudge. It strongly encourages a story-based rather than rule-based RPG campaign. Players don’t even have ability numbers, they have various strengths or aspects (that can be quite poetic), and players use those aspects along with simple die roll modifications to (practically speaking) convince the referee to allow such-and-such to happen. If you’re interested in story-based RPGs, I strongly recommend you read Fate (version 2.0 is a free download: http://www.faterpg.com/resources/ ). (Don’t confuse it with the computer game Fate.)

(Spoilers follow if you haven’t seen the fourth Indiana Jones movie.)

The extreme version of story-based RPGs, something that appears to be more and more popular and which Fate could easily be used for, is the cinematic campaign. In such campaigns it would be quite normal for characters to take actions that one might see in tentpole adventure movies.

The best example I can think of is Indy’s survival of a nuclear blast because he hides inside a refrigerator. The force of the blast that launched the refrigerator Lord-knows-how-far would have killed him, the shock when it hit the ground would’ve killed him, and there’s no way it could have stayed closed during the “flight” and yet open easily after coming to rest. But in a movie we just kind of accept it and move on, because we knew it was going to be fantastical before we went to it. Yes, there are lots of people who would never bother with an Indiana Jones movie because they know it’s fundamentally nonsensical, but also lots who ignore the silliness of it and love to watch.

TV programs like Lost routinely also veer into the land of unbelievability. Don’t get me wrong, fantasy can be quite believable if you begin with the assumption that magic exists; I’m talking about events that occur in a story that are so astronomically unlikely that they’re unbelievable no matter what the technological/magic parameters of the setting.

Teenagers often play fantastical RPGs, which I have tended to call “brain fever”. Whatever you could hatch in your feverous brain, the referee might go along with!

In a cinematic RPG the players would argue about how wonderful their character was in this nuclear refrigerator situation and persuade the referee to give them some chance to survive. While in reality the chance is ridiculously astronomical (if I even bothered I’d say “role 10 d10s and if you get a 10 on all of them you survive but are so badly hurt you’re unable to move”), more typically the referee will give a significant though small chance such as 1 in 100 or even 1 in 20.

Players might argue that their RPG characters are much tougher than a normal person (Indiana Jones is far tougher than a normal person, but not a superhero). Because of that “magical” toughness their character should be able to survive in the refrigerator. It doesn’t really matter that the refrigerator itself would be unlikely to survive. . . Sure.

As you can see from my example, I would not be a suitable referee for a cinematic RPG. The ridiculousness of what was going on would offend me, and if I bothered to give any chances at all they would be truly astronomical. But some of that may come because I treat D&D (the only RPG I play) as a kind of cooperative wargame, not as a storytelling engine. The cinematic D&Ders are clearly playing for story, not for gameplay.

Games like Fate remind me of one well-known wargamer’s view of RPGs: he feels they are too “loosey-goosey”, he wants to know what he can and cannot do. Games like Fate are much more like miniatures rules, which seem to require constant negotiation anyway (as another well-known wargamer said), than like boardgame rules which are supposed to define all possibilities. I think a cinematic RPG will work better if it's less precise, if more comes from the players and less from the referee, and less yet from the rules. Or as they say in “Pirates of the Caribbean,” the rules are actually more like guidelines . . .

I think part of the unbelievable cinematic play derives from a widespread failure to understand probability and large numbers. To most people one large number is as good as another even if one is 10,000 times more than the other. They don’t seem to understand that 1 in 100 is immensely different from 1 in a million (or even 1 in a thousand), which is in turn immensely different from 1 in a billion. And your average person has no clue about probabilities.

But a bigger part probably may come from what I see as the great increase in game-playing as escapism in the form of wish-fulfillment. Players don’t want to be limited, they want to get away from reality, the want to feel powerful and heroic, so a cinematic game can suit their feelings and purposes.

Wargames require mental (not physical) concentration, movies don’t. (In contrast many computer games require physical concentration, except even if you die you just respawn or go back to a save . . .) Wargame-style tabletop RPGs inevitably will become less popular over time, while story-style will become more popular, as people tend with passing generations to concentrate less on a particular thing. It’s a trend seen in TV, the theater, and computer games as well as many other parts of life, so why wouldn’t it affect RPGs as well? If the story style of play takes direction from the players and the rules, rather than depending heavily on the referee, then it’s as practical as the wargame style. In fact, for the wargame style the referee needs to master many rule details, while the story style can be much less precise, and that may appeal to many referees.

To go back to the Expo, I was looking at Cubicle 7s 600+ page large-format hardcover books. Why, I asked myself, would younger people especially, who normally don’t read books, buy such enormous tomes? I asked Sarah about the demographics of Cubicle 7's market, and she answered 25 to 40 years old. So that includes lots of Gen Xers and the older millennials, perhaps beyond the age of the millennials who are famous for the acronym “tl;dr” (too long; didn’t read). On the other hand, millennials will read a lot when they really get into something, but that kind of enthusiasm is uncommon.

The only reason I can think of for good sales is that these books are bought as a substitute for imagination. It is often suggested that young people don’t use their imaginations much because for many, many years now stories have been presented to youngsters whole cloth, with visuals. Their toys are from particular stories, video games have the stories built-in, television and movies are everywhere, and so youngsters have rarely had to figure out stories on their own. They aren’t, for example, presented with the challenge of making paper boats and then figuring out what to do with them. Any boats they have are ready-made and associated with specific stories. So in RPGs they’re much more likely than my generation (boomers) to use something imagined by someone else rather than to imagine it themselves.

I’ll interject a related observation here. A few years ago I attended a talk by Monte Cook of D&D fame at the Origins Game Fair. At one point he observed that published D&D adventures spend a lot more time on story than in the past, and wondered why. My answer is that people don’t buy the adventures to play them so much anymore, they buy them to read them, and they want to read a story with a plot rather than just read about a situation. The buyers can then take whatever aspects of the story they like and incorporate them into the stories that they are telling in their own games, and they can also incorporate the game ideas they get into their adventures, but most of the time they don’t use the entire published adventure. There are so many inexpensive published adventures now that few people would have time to use even a small fraction, so they’re often bought to be read, not played.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)