Thoughts about some game-related topics that are not long enough for separate blog posts.

**

I will be at PrezCon in Charlottesville, VA from Thursday through Sunday. I'm scheduled to give a talk and question/answer session about game design at 9PM Friday.

**

We've been talking about depth in games, and how games and gamers have changed. The following quote from Dame Eileen Atkins, a famous British stage actress ("Dame" is the female equivalent of "Sir"), provides some backup for what I've been saying, from an entertainment realm other than games. She was talking to a newspaper writer in New York in October 2003, more than eight years ago now:

"In England, as here, there are always two kinds of audiences: the Royal Shakespeare and the West End. In the last 10 years, audiences have been changed by television. One can tell: people don't concentrate and they expect lighter fare - and I do hate disappointing the audiences. One lady came up to me afterwards here [NY], very complimentary, and then she said 'Well, this is terribly heavy.' And I thought 'Oh dear, you think this is heavy? Because it isn't, it's just serious.'"

Gameplay depth, which requires concentration and planning and some attention to detail, tends to be "terribly heavy" entertainment these days.

**

"Copy-cat" games--direct, blatant clones--are a big problem in the video game industry, especially the small games popular on Apple iOS. For example see http://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2012-02-06-apple-removes-cloned-games-from-app-store . Long ago, Diplomacy was cloned in Brazil (with the addition of a supply center somewhere in the south, I think). I recall seeing an ad a couple years ago for a game called something like "Tetris the Strategy Game" that was clearly a blatant copy of Blokus, but I don't follow publishing closely enough to hear of other examples of cloning. Is cloning becoming a problem on the tabletop?

**

5th edition D&D is supposed to unify the editions so that players can customize the game to suit their tastes, whatever edition they prefer. But I notice that to comment on Monte Cook's discussions, you must be a subscriber to D&D Insider, so people who aren't 4e fans (Insider subscriptions are for 4e players) are excluded.

**

"Multiplayer solitaire" is usually a case of a puzzle that's been turned into a contest. A contest is any activity that can be timed or assigned points, or measured in some other way (as in how far a coin falls from a wall or how far one can throw a baseball). If two or more people try to beat one another's performance in this, and have no way to hinder or help other participants, then you have a contest. Another example, type for five minutes and whoever types the most words wins the contest.

Races are much like contests, but include some method (if only blocking) to hinder an opponent.

Contests, in and of themselves, are not games. There is no design involved. Games and puzzles require design.

**

For generals and admirals, war is a lot of risk-taking in the face of high uncertainty. There's sometimes a strong element of "yomi", reading the intentions of the other side and taking advantage of that. Chess, in contrast, is full of certainty, with nothing hidden other than the intentions of the other player.

This is one of the big problems with wargames: if they truly reflect conditions in war, they're games with a lot of chance and yomi, and that's not what some game players want. I was attracted to Stalingrad and Afrika Korps, 50 years ago, because I was able to have some control over what went on, it was something like war but also something like chess. It was "strategic". But it wasn't anything like a real war. (Of course, you can say NO boardgame is going to be anything like a real war . . .)

As Patrick Carroll says, "Chess players have the advantage of lots of 'live practice.' Generals don't. There just aren't enough wars. Of course, this relates to the issue of friction, that study does not equal reality. "

**

Someone tweeted "sometimes I feel like @lewpuls just doesn't like euro games, and he tries to justify this by denigrating them."

Say what? Obviously I don't care for them as a category. No, I don't have many good things to say about them. Yet I certainly have no need to "justify" my dislike, any more than I need to justify dislike of coconut or extremely horrific movies or regular-season baseball. Did the poster assume that Euros are "good" and anyone who dislikes them has to justify being "ungoodthinkful", as Orwell would say?

The odd thing is that some people (not necessarily this tweeter) take it personally. If you like the kinds of games you like, what the hell do you care what someone else says? I don't frenetically blast away as Michael Barnes used to (eloquent as he could be), I try to explain. But not over and over when someone is convinced that I'd like the games if I just really understood them. I do understand them, and I don't like them, *as a category*. They do not supply what I am looking for in games, in fact for me many of them are much closer to puzzle-contests than to games. I don't much like puzzles.

**

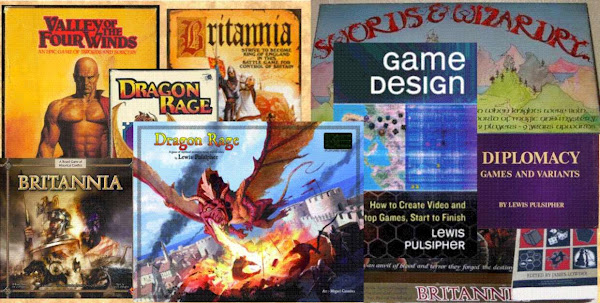

I received a PDF of McFarland's spring 2012 catalog listing my book "Game Design: How to Create Video and Tabletop Games, Start to Finish". I'm guessing it will be out in spring or summer; at this point I have not received galleys nor have I made the index. Web site at http://www.mcfarlandpub.com/book-2.php?id=978-0-7864-6952-9 .

Why would you read a book? When I was a kid in the 50s and 60s, as for generations before, a book was a treasure trove of information, something to be read carefully and absorbed as much as possible. While the book is no longer the absolute treasure trove, it still organizes information in an easily digestible form. But more important, a book can convey the experience of the author to the reader, and if that experience is valuable then this is something the reader won't get anywhere else. A major purpose for me in writing the book is to help beginning game designers avoid the "school of hard knocks" that I had to go through, applying my experience in teaching novice game designers as well.

Nowadays people are much less impressed by books because there are so many other sources of information, but if you really want to learn about something in depth a good book is probably the best way to do it other than having an experienced person teach you directly.

**

The Web and computing in general have brought about a mindset that "digital should be free". Fortunately tabletop gaming is relatively immune to this, because a tabletop game is a very tangible product. But what will happen in the long run with video games, especially now that so many are free-to-play? Will the "digital should be free" mindset ultimately drive many of the AAA video game makers out of the AAA business because they won't be able to successfully charge $60 or so for a game? If it does happen, that won't necessarily be a Good Thing, but market forces often cause Bad Things to happen.

**

I was the guest on the Ludology podcast #26 about epic tabletop games (not about the video game company). It was posted Feb 19 (find it on BGG or search for "Ludology podcast site"). Ludology is the only podcast I listen to, because it's about "the why of games", not about new games or community chit-chat or fanboyism.

**

I am gradually extracting my old articles from various game magazines to compile three novel-sized books. Often because of poor scanning or weak OCR I have to make quite a few corrections so I'm reading some of it as I go along. It's always interesting to read something that you wrote as much as three decades before, though I'm glad to say that I usually agree with myself. :-) Most of what I'm working on is RPG material and I see that much has stayed the same over three decades.

**

I need to find a 50-60 year old dictionary and look at the definition of "trial and error". To me it means guessing at a solution, trying it, and then if it doesn't work, guessing at another and trying--until you get lucky and guess right. But dictionary definitions now are broad enough that the scientific method, which is quite different from guessing, could be called trial and error. Someone suggested the substitute phrase "guess and check", so that's what I'll try to use from now on. "T&E" appears to be yet another phrase whose meaning has changed significantly over time.

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Tuesday, February 07, 2012

The Fundamental Differences between Board and Card Games and How Video Games Tend to Combine Both Functions

What are the fundamental functional differences between boardgames and card games? I’m not sure how important this question is from a game player’s point of view but it’s certainly important for game designers (even for video game designers). The obvious physical format is important, but now that we can convert physical non-electronic games to electronic formats the lines are less clear. More importantly, each type of game emphasizes or encourages different kinds of challenges and gameplay, regardless of the physical format.

It’s also possible to take a game that originated in one format and make something like it in the other format. I have done this with a dungeon delving game and even made a prototype version of Britannia using cards. I believe this happens a fair bit in the Eurostyle games. For example, San Juan is a card game based on Puerto Rico, and so is Race for the Galaxy. But as we’ll see many Eurostyle boardgames do not use a board in the traditional way, for maneuver and location, instead they use the board to keep track of other information. So what is the traditional way?

The most important difference between the two kinds of games is that card games are inherently games of hidden information and boardgames are inherently games of maneuver and location. (When I say location I mean the location of actual pieces, not a representation of some virtual commodity such as the amount of money you have or the amount of victory points. “Location” implies maneuver or placement.)

Card Games

By their nature cards make it easy to hide information. The information is often hidden from all the players, but commonly in card games one player has some information that none of the other players can access: the cards in his hand and what they can be used for and what they can do. Anyone who has played many card games has encountered this usage again and again.

There are exceptions. The traditional card game Bridge is unusual insofar as, after bidding, one player’s cards are revealed (the dummy). And this tells the Dummy’s partner what cards his opponents have, though not which individual opponent has which cards. Texas Hold ‘em is another card game where some of the information is revealed to everyone and only two cards per player are hidden from the other players. But Five Card Draw poker hides all the cards, sometimes even after the game ends.

Hobby card games such as Bang!, Atlantic Storm, Brawling Battleships, and Lost Cities have hands of cards but some cards are placed on the table so that they can affect everyone in the game.

Boardgames

Most really old traditional board games are games location and maneuver-mancala, chess, checkers, Nine Men’s Morris, Parcheesi, backgammon, Go, and Japanese/Chinese forms of chess. In some of these games there is only placement (and removal) of pieces, for example in Go. In others the initial placement is predetermined and the game is all about maneuver, as in chess or checkers. There are few games that include both placement and maneuver.

Notice that few of these old games use dice. Dice provide uncertainty within a range of possibilities, a kind of hidden information but not the same kind as we get with cards. Dice were the typical way to provide uncertainty before games could include cards. Handmade playing cards first entered Europe in the late 14th century. The technology to make uniform decks of cards did not exist until the invention of printing, so the really old traditional games do not use cards.

Card games are probably more popular than boardgames for a variety of reasons. First they’re less expensive, second they tend to take less time to play, third they can be more colorful than boardgames because of the artwork on each card. Most important perhaps, the hidden information tends to make it harder for a planner-style player to dominate play, introducing elements of uncertainty and chance that make it possible for a less calculating player, or perhaps I should say one who is less a classical/planner player, to win a minority of the time. Another way to put this is that casual players have a better chance of winning in hidden information games than in games of perfect information, most traditional boardgames being perfect information games.

Hybrids

It is possible to use cards to create the equivalent of a board, but then we have something that is functionally a boardgame not a card game. I have done this in two prototypes were my objective was to make a game with only cards as components (to simplify production), yet I wanted to have maneuver and location. Many games that now use cardboard tiles to create a board on the table would once have used cards for the same purpose. While we might think of these as boardgames, such as Settlers of Catan and Betrayal at House on the Hill, they could have been produced with cards, and in the latter game the tiles are used to hide information in the same way that cards hide information before they are drawn from a deck. Tikal and Carcassonne do the same kind of thing. Settlers uses the board for placement, Betrayal uses it for maneuver, Carcassonne uses the “board” as the unit of placement rather than placing pieces on a board.

In a boardgame location and maneuver tend to dominate play. Chess, checkers, backgammon, even Parcheesi, are games of maneuver. Hex and counter wargames are typically games of maneuver, though we also have combat and chance elements in dice rolling. Monopoly is not a game of maneuver because you have no control over where you go, but there is the element of location. In Tic-Tac-Toe (Noughts and Crosses) you don’t actually move pieces once you put them on the board but where you put them is vitally important.

Race games (getting to a finish line before anyone else) are generally about maneuver and location, whereas speed contests (something is timed individually and best time wins) are not.

You can introduce an element of hidden information into boardgames, of course. This is not new. More than a century ago we had a variation of chess called Kriegspiel where each player could only see his own pieces and a referee told a player when an opposing piece took his piece or checked his King. While the phrase “block games” tends to put one in mind of the wargames published by Columbia Games, the technique goes back at least to the game L’Attaque patented in 1909, more familiar in the copycat game Stratego. The Columbia games add dice and more complex boards to the equation but the key element is hiding some of the information that normally is exposed everyone in a boardgame.

Flat (cardboard/chipboard) pieces that are placed face down introduce another element of hidden information.

In contrast to typical boardgames, many Eurostyle games include boards that are not used for maneuver or even for location. The board is used to help keep track of other kinds of information. Player layouts for tracking amounts of virtual commodities are small boards. But even in games with larger boards, the board may not represent location or present opportunities for maneuver. Kingsburg is an example.

Actual warfare is a combination of hidden information and maneuver, among other things. Given the prominence of maneuver in warfare, it’s not surprising that board wargames are much more common than card wargames.

Games that are neither type

There are many games that are not primarily either hidden information games or location and maneuver games. Some Euro games that have lots of parts and cards and boards are primarily games of resource management– Puerto Rico for example. There is neither maneuver nor much hidden information, though there is uncertainty. Resource management depends on hidden information and uncertainty. Uncertainty can come from many places, but mainly comes from the players, hidden information, or dice or other random elements (which cards can also provide).

Auction games aren’t really either type, though they lean toward hidden information more than location and maneuver. You can argue that resource management comes down to set collection, just as auction games do.

Further afield we have games of deduction (which is largely about hidden information, though Clue/Cluedo includes location and maneuver as well). It might be nice if we could pigeonhole all games into a very few slots like “hidden information”, “resource management”, “location and maneuver”, and “auctions”. But I don’t think this is practical, at any rate I see too many exceptions to almost any set of categories at this point.

Collectible card games are largely about hidden information, though some have an element of location (cards face up on the table) just as some traditional card games do.

Tabletop RPGs involve both maneuver and hidden information in abundance. They are closer to video games than to either board or cardgames.

Competition in board and card games

It's fashionable in the hobby tabletop game industry to produce "Eurostyle" games that reduce direct conflict between players to a minimum. They are often more like puzzles that have been turned into speed contests, not games, and "multi-player solitaire" is a common description of many tabletop games. Wargames, on the other hand, emphasize competition and confrontation, of course.

Mark Johnson suggested in a recent "Ludology" podcast that card games are less competitive than boardgames. Is that so, and why? I think it is. Because boardgames are naturally about maneuver and location, they tend to involve more direct interaction than cards, where you can play cards onto the table and do very little to affect other players. Traditional boardgames tend to involve tearing down the opposition, not building up, you start with some pieces and lose them as the game goes along. (Even in Go, where you add pieces to the board, you're taking your opponent's pieces as well. Go is not much like other traditional boardgames, in any case.) Traditional card games usually involve building up sets or tricks. You start with nothing but a hand of cards and gradually build up your position.

In more-than-two-sided boardgames the system of maneuver and location often means that you are not able to attack/hinder all the opponents, because some are too far away. In more-than-two-sided card games you do have a player on your right and on your left, and the rules may allow you to attack only those players, or "anyone".

Video Games

We can ask what the nature of video games is in comparison to card and boardgames. First, it’s relatively easy to make a computer game where most of the information is hidden from the player or players, a card game characteristic. When you program a video game you have to deliberately decide to show information to the player, or he’ll know nothing.

That information can be shown on the equivalent of a board, though the board can be rather more complex than a physical board. Pac-Man is a quintessential game of maneuver, as is Space Invaders. Civilization uses a board, a square grid through Civilization IV and a hex grid in Civilization V (version V generally exhibits a greater influence from board wargames).

Many “strategy” video games appear to be games of maneuver, for example Starcraft and Civilization. Hidden information is also quite dominant. But there are so many layers of production and technology involved that these games are more about resource management than either maneuver or hidden information. When cut down to a simple version as a social network game, Civilization becomes almost entirely a resource management game.

A video platformer is a game of maneuver. An old-style text adventure game is a game of hidden information. Yes there is more to both, especially to the old-style adventures, but these are the major delineations.

The abstract game Tetris is a game of maneuver much more than a game of hidden information. Bejeweled is a game of location and maneuver insofar as you move gems in order to cause groups of gems to disappear. Shooters are games of location and maneuver as well as games of hidden information.

What video games are particularly good at is combining the two major elements of board and card games together as in shooters and real-time or turn-based strategy games.

It’s also possible to take a game that originated in one format and make something like it in the other format. I have done this with a dungeon delving game and even made a prototype version of Britannia using cards. I believe this happens a fair bit in the Eurostyle games. For example, San Juan is a card game based on Puerto Rico, and so is Race for the Galaxy. But as we’ll see many Eurostyle boardgames do not use a board in the traditional way, for maneuver and location, instead they use the board to keep track of other information. So what is the traditional way?

The most important difference between the two kinds of games is that card games are inherently games of hidden information and boardgames are inherently games of maneuver and location. (When I say location I mean the location of actual pieces, not a representation of some virtual commodity such as the amount of money you have or the amount of victory points. “Location” implies maneuver or placement.)

Card Games

By their nature cards make it easy to hide information. The information is often hidden from all the players, but commonly in card games one player has some information that none of the other players can access: the cards in his hand and what they can be used for and what they can do. Anyone who has played many card games has encountered this usage again and again.

There are exceptions. The traditional card game Bridge is unusual insofar as, after bidding, one player’s cards are revealed (the dummy). And this tells the Dummy’s partner what cards his opponents have, though not which individual opponent has which cards. Texas Hold ‘em is another card game where some of the information is revealed to everyone and only two cards per player are hidden from the other players. But Five Card Draw poker hides all the cards, sometimes even after the game ends.

Hobby card games such as Bang!, Atlantic Storm, Brawling Battleships, and Lost Cities have hands of cards but some cards are placed on the table so that they can affect everyone in the game.

Boardgames

Most really old traditional board games are games location and maneuver-mancala, chess, checkers, Nine Men’s Morris, Parcheesi, backgammon, Go, and Japanese/Chinese forms of chess. In some of these games there is only placement (and removal) of pieces, for example in Go. In others the initial placement is predetermined and the game is all about maneuver, as in chess or checkers. There are few games that include both placement and maneuver.

Notice that few of these old games use dice. Dice provide uncertainty within a range of possibilities, a kind of hidden information but not the same kind as we get with cards. Dice were the typical way to provide uncertainty before games could include cards. Handmade playing cards first entered Europe in the late 14th century. The technology to make uniform decks of cards did not exist until the invention of printing, so the really old traditional games do not use cards.

Card games are probably more popular than boardgames for a variety of reasons. First they’re less expensive, second they tend to take less time to play, third they can be more colorful than boardgames because of the artwork on each card. Most important perhaps, the hidden information tends to make it harder for a planner-style player to dominate play, introducing elements of uncertainty and chance that make it possible for a less calculating player, or perhaps I should say one who is less a classical/planner player, to win a minority of the time. Another way to put this is that casual players have a better chance of winning in hidden information games than in games of perfect information, most traditional boardgames being perfect information games.

Hybrids

It is possible to use cards to create the equivalent of a board, but then we have something that is functionally a boardgame not a card game. I have done this in two prototypes were my objective was to make a game with only cards as components (to simplify production), yet I wanted to have maneuver and location. Many games that now use cardboard tiles to create a board on the table would once have used cards for the same purpose. While we might think of these as boardgames, such as Settlers of Catan and Betrayal at House on the Hill, they could have been produced with cards, and in the latter game the tiles are used to hide information in the same way that cards hide information before they are drawn from a deck. Tikal and Carcassonne do the same kind of thing. Settlers uses the board for placement, Betrayal uses it for maneuver, Carcassonne uses the “board” as the unit of placement rather than placing pieces on a board.

In a boardgame location and maneuver tend to dominate play. Chess, checkers, backgammon, even Parcheesi, are games of maneuver. Hex and counter wargames are typically games of maneuver, though we also have combat and chance elements in dice rolling. Monopoly is not a game of maneuver because you have no control over where you go, but there is the element of location. In Tic-Tac-Toe (Noughts and Crosses) you don’t actually move pieces once you put them on the board but where you put them is vitally important.

Race games (getting to a finish line before anyone else) are generally about maneuver and location, whereas speed contests (something is timed individually and best time wins) are not.

You can introduce an element of hidden information into boardgames, of course. This is not new. More than a century ago we had a variation of chess called Kriegspiel where each player could only see his own pieces and a referee told a player when an opposing piece took his piece or checked his King. While the phrase “block games” tends to put one in mind of the wargames published by Columbia Games, the technique goes back at least to the game L’Attaque patented in 1909, more familiar in the copycat game Stratego. The Columbia games add dice and more complex boards to the equation but the key element is hiding some of the information that normally is exposed everyone in a boardgame.

Flat (cardboard/chipboard) pieces that are placed face down introduce another element of hidden information.

In contrast to typical boardgames, many Eurostyle games include boards that are not used for maneuver or even for location. The board is used to help keep track of other kinds of information. Player layouts for tracking amounts of virtual commodities are small boards. But even in games with larger boards, the board may not represent location or present opportunities for maneuver. Kingsburg is an example.

Actual warfare is a combination of hidden information and maneuver, among other things. Given the prominence of maneuver in warfare, it’s not surprising that board wargames are much more common than card wargames.

Games that are neither type

There are many games that are not primarily either hidden information games or location and maneuver games. Some Euro games that have lots of parts and cards and boards are primarily games of resource management– Puerto Rico for example. There is neither maneuver nor much hidden information, though there is uncertainty. Resource management depends on hidden information and uncertainty. Uncertainty can come from many places, but mainly comes from the players, hidden information, or dice or other random elements (which cards can also provide).

Auction games aren’t really either type, though they lean toward hidden information more than location and maneuver. You can argue that resource management comes down to set collection, just as auction games do.

Further afield we have games of deduction (which is largely about hidden information, though Clue/Cluedo includes location and maneuver as well). It might be nice if we could pigeonhole all games into a very few slots like “hidden information”, “resource management”, “location and maneuver”, and “auctions”. But I don’t think this is practical, at any rate I see too many exceptions to almost any set of categories at this point.

Collectible card games are largely about hidden information, though some have an element of location (cards face up on the table) just as some traditional card games do.

Tabletop RPGs involve both maneuver and hidden information in abundance. They are closer to video games than to either board or cardgames.

Competition in board and card games

It's fashionable in the hobby tabletop game industry to produce "Eurostyle" games that reduce direct conflict between players to a minimum. They are often more like puzzles that have been turned into speed contests, not games, and "multi-player solitaire" is a common description of many tabletop games. Wargames, on the other hand, emphasize competition and confrontation, of course.

Mark Johnson suggested in a recent "Ludology" podcast that card games are less competitive than boardgames. Is that so, and why? I think it is. Because boardgames are naturally about maneuver and location, they tend to involve more direct interaction than cards, where you can play cards onto the table and do very little to affect other players. Traditional boardgames tend to involve tearing down the opposition, not building up, you start with some pieces and lose them as the game goes along. (Even in Go, where you add pieces to the board, you're taking your opponent's pieces as well. Go is not much like other traditional boardgames, in any case.) Traditional card games usually involve building up sets or tricks. You start with nothing but a hand of cards and gradually build up your position.

In more-than-two-sided boardgames the system of maneuver and location often means that you are not able to attack/hinder all the opponents, because some are too far away. In more-than-two-sided card games you do have a player on your right and on your left, and the rules may allow you to attack only those players, or "anyone".

Video Games

We can ask what the nature of video games is in comparison to card and boardgames. First, it’s relatively easy to make a computer game where most of the information is hidden from the player or players, a card game characteristic. When you program a video game you have to deliberately decide to show information to the player, or he’ll know nothing.

That information can be shown on the equivalent of a board, though the board can be rather more complex than a physical board. Pac-Man is a quintessential game of maneuver, as is Space Invaders. Civilization uses a board, a square grid through Civilization IV and a hex grid in Civilization V (version V generally exhibits a greater influence from board wargames).

Many “strategy” video games appear to be games of maneuver, for example Starcraft and Civilization. Hidden information is also quite dominant. But there are so many layers of production and technology involved that these games are more about resource management than either maneuver or hidden information. When cut down to a simple version as a social network game, Civilization becomes almost entirely a resource management game.

A video platformer is a game of maneuver. An old-style text adventure game is a game of hidden information. Yes there is more to both, especially to the old-style adventures, but these are the major delineations.

The abstract game Tetris is a game of maneuver much more than a game of hidden information. Bejeweled is a game of location and maneuver insofar as you move gems in order to cause groups of gems to disappear. Shooters are games of location and maneuver as well as games of hidden information.

What video games are particularly good at is combining the two major elements of board and card games together as in shooters and real-time or turn-based strategy games.

Thursday, February 02, 2012

Some distinctions between types of war-related games

One of the disadvantages of writing articles for magazines, such as “Against the Odds,” is that it can be literally years from the time it is submitted to the time it is published. I recently sent ATO an article about different kinds of war related games, and I’m going to briefly categorize its 4,000 words in 400.

I will not respond to any comments here, sooner or later the full article will be published.

Joe Angiolillo’s taxonomy of war related games:

● Games about war

● Wargames

● Simulations

Games about war

● no connection with reality

● symmetric

● no variation in terrain and units

● no representation of actual or even fictional events

● no attempt to tell a story

Games such as Conflict, Risk and Chess fall into this category.

Wargames

● asymmetric

● variation in terrain and units

● real or fictional event is depicted

● there is an explicit story involved (remember "story" is part of hisSTORY)

Simulations

● wargames taken to an extreme

● term papers with board and pieces and no concern for play balance

● more or less forces particular outcomes in order to match history

Now a different distinction, between war game (two words) and battle game:

War game

● the heart is economy

● ultimate objective is to improve your economic capacity and destroy the enemy's

● for two players, occasionally for more than two

● cover years or even centuries

● territory usually equates to additional forces, following the age-old principle that land equals wealth

● more likely to use areas (like a normal map)

● generally large-scale and strategic

Battle game

● no economy, instead an order of appearance

● ultimate objective is to destroy opposing units because they cannot get more

● intermediate objective (e.g. territorial, or even “capture the king”) as a victory avoids much of the tedium of destroying units

● almost always for two players

● usually cover a few days to a year or so

● territory is only useful for the terrain and geopolitical implications

● usually maneuver-focused, and often use a hex or square grid

● generally smaller scale and tactical/grand tactical

Finally another category:

Conquest games (Risk, History of the World, Vinci/Smallworld)

● can be either war or battle game, usually war

● are usually in Joe’s “Games about war” category

● very few "realistic" or real world restrictions on what you can do--"freedom to do whatever you want"

● attacker can always get the upper hand (odds favor those who attack-attack-attack), so it’s not strategically wise to play defensively

● usually symmetrical

● typically large scale

● combat typically very simple

● particularly attractive type of game related to war for those who aren’t hobby gamers

Take it as it is, please, I am not at liberty to discuss it further.

I will not respond to any comments here, sooner or later the full article will be published.

Joe Angiolillo’s taxonomy of war related games:

● Games about war

● Wargames

● Simulations

Games about war

● no connection with reality

● symmetric

● no variation in terrain and units

● no representation of actual or even fictional events

● no attempt to tell a story

Games such as Conflict, Risk and Chess fall into this category.

Wargames

● asymmetric

● variation in terrain and units

● real or fictional event is depicted

● there is an explicit story involved (remember "story" is part of hisSTORY)

Simulations

● wargames taken to an extreme

● term papers with board and pieces and no concern for play balance

● more or less forces particular outcomes in order to match history

Now a different distinction, between war game (two words) and battle game:

War game

● the heart is economy

● ultimate objective is to improve your economic capacity and destroy the enemy's

● for two players, occasionally for more than two

● cover years or even centuries

● territory usually equates to additional forces, following the age-old principle that land equals wealth

● more likely to use areas (like a normal map)

● generally large-scale and strategic

Battle game

● no economy, instead an order of appearance

● ultimate objective is to destroy opposing units because they cannot get more

● intermediate objective (e.g. territorial, or even “capture the king”) as a victory avoids much of the tedium of destroying units

● almost always for two players

● usually cover a few days to a year or so

● territory is only useful for the terrain and geopolitical implications

● usually maneuver-focused, and often use a hex or square grid

● generally smaller scale and tactical/grand tactical

Finally another category:

Conquest games (Risk, History of the World, Vinci/Smallworld)

● can be either war or battle game, usually war

● are usually in Joe’s “Games about war” category

● very few "realistic" or real world restrictions on what you can do--"freedom to do whatever you want"

● attacker can always get the upper hand (odds favor those who attack-attack-attack), so it’s not strategically wise to play defensively

● usually symmetrical

● typically large scale

● combat typically very simple

● particularly attractive type of game related to war for those who aren’t hobby gamers

Take it as it is, please, I am not at liberty to discuss it further.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)